Getty Images

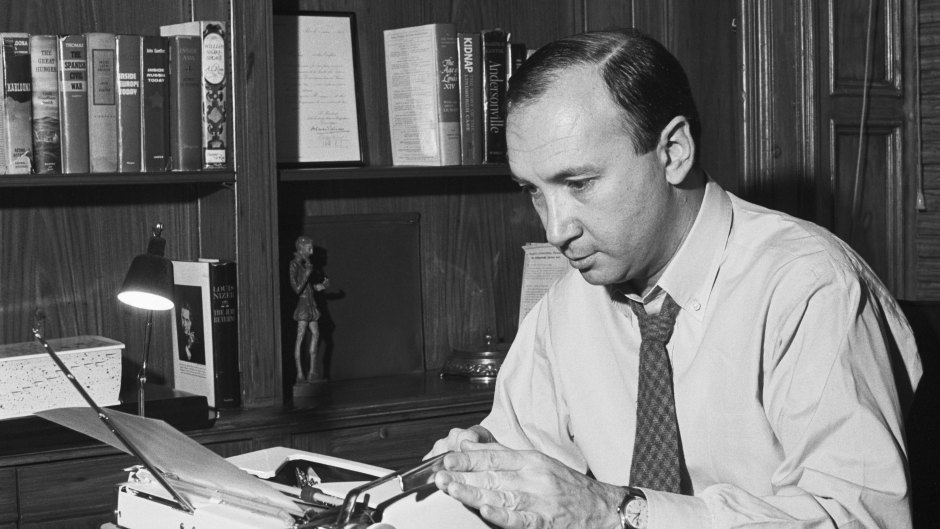

‘Odd Couple’ Creator Neil Simon Remembered in a Newly Recovered Interview (EXCLUSIVE)

There are a lot of people who, until this past weekend, probably weren’t as familiar with the name Neil Simon as others once had been. Yes, he has a Broadway theater named after him (home in the past couple of years to revivals of Cats and Angels in America, and the forthcoming tribute musical, The Cher Show), but his last play was 2003’s Rose’s Dilemma and his last movie script was 1998’s The Odd Couple II. In recent years, unfortunately, he has battled a number of health issues that ultimately took his life at the age of 91 on Sunday, Aug. 26.

The passing of Neil, if you’ll pardon the personal tangent, impacts on two levels. First of all, in 1965 he wrote the Broadway play The Odd Couple, which was adapted to the big screen three years later and which captured my then eight-year-old imagination. Following that was no less than three live action TV series, a Saturday morning cartoon, a female version of the play on Broadway, and innumerable stage productions mounted around the world. Simply put, The Odd Couple has been a part of my pop culture life for most of it (not to mention the fact that his 1977 film The Goodbye Girl, starring Richard Dreyfuss and Neil’s then-wife, Marsha Mason, remains one of my all-time favorites as well).

Another part of the equation for me is that back in 1981, I was a student at Hofstra University and a writer for the campus newspaper, The New Voice. That year, Neil was awarded a Doctor of Humane Letters from the university, and I was given the assignment to head into NYC to his apartment to conduct an interview. When I heard about his death this weekend, I decided to explore my personal archives (AKA the basement, where dozens of boxes of old cassette tapes are stored) and managed to find that particular conversation, the sound quality of which had held up pretty well. I’m talking about the tape’s sound, not my own. Playing it back, I heard exactly what it was at the time — a 21-year-old kid who had just started doing interviews, was a nervous wreck, hadn’t prepared nearly enough questions, and was face to face with a writing legend. Yet somehow I managed to struggle through.

Things kicked off with a discussion of his play Fools, described as a comic fable, which had run for only 40 performances between April and May of 1981. In response, it was reported that he planned on opening future plays Off-Broadway to gauge audience reactions. When asked about this, he actually expressed his frustrations with the way theater was changing, which, interestingly enough, is probably more true today than ever.

“Two years ago,” he explained, “we did a musical called They’re Playing Our Song, which has two main characters, six others, multiple sets, an orchestra, and cost us $800,000 to do. Fools is just a straight play without music or multiple sets, but cost us $600,000 to produce. So in just two years you can see the difference in cost. Also, the theater is moving away from plays. Audiences want to see musicals and the artistry that goes into making them. I have seen musicals that have opened recently that aren’t one-tenth as good as, say, Woody Allen’s last play or, more immodestly, my own, but they’ve got music in them. If Fools had 10 songs, it would still be running.”

I’d pointed out that during the 1979 Academy Awards, host Johnny Carson joked that the ceremonies were taking so long that Neil had written a new play backstage. Being a newbie, I jumped in with the most obvious question you could imagine: “Where do you get so many ideas?” (admittedly winced hearing that one back).

“I don’t know where they come from,” he admitted. “I’m never aware of the genesis of a play. Sometimes they’re inspired by real life incidents in my or somebody else’s life, which was the case with The Odd Couple. It actually happened to my brother and a friend of his, who were living together and going through all that. I feel Chapter Two made a good play, because I think that people who have lost somebody and don’t know how to take the next step would benefit from it. It was also a cathartic thing to get that out. The Goodbye Girl is something else. There was no inspiration. I wanted to write a script for my wife, Marsha, and Richard Dreyfuss, because I thought that they would make a terrific combination. I said, ‘Okay, who is she? What does he do? What is the conflict? How do they meet?’ More plays have probably been written that way than some who say, ‘Ah, I’ve got this great idea for a play!’”

This was immediately followed by my wondering if he’s ever been a victim of writer’s block (hey, I never said these were riveting questions). “A little, but not a lot,” Neil said. “I’ve had writer’s block on particular projects when I suddenly saw a play had reached a dead end, and there was really nowhere else to go. It’s not that I get a block, but you get a realization that you’ve reached a dead end and you can’t think of something. A block comes from fear of whether it’s any good or if anybody is going to like it. These seem to be the years of flowing creativity for me. I can think of more ideas and sometimes I write them and just throw them away. I just finished what was supposed to be a two-act play. I finished the first act, started the second and suddenly lost faith in it. I just put it in the drawer, but that’s happened before. Barefoot in the Park and The Sunshine Boys were in the drawer for over a year. I thought I’d never do them again, but I reread them and thought that they were really good and wondered why I had put them away in the first place.”

One that went away and never saw the light of day again was Mr. Famous, his script for the intended sequel to The Goodbye Girl. As did a planned TV series version of the first film.

“I wrote the script and got Marsha, Richard, and Quinn Cummings [who played Marsha’s daughter], and we sat down for the reading,” he said of Mr. Famous. “But I said, ‘Forget it,’ because it was not sympathetic. You didn’t root for it. You rooted for The Goodbye Girl, because you wanted her to get him, and him to get his career. You wanted their lives fulfilled. In the sequel, his life is fulfilled and he’s a major star. People wouldn’t be able to identify with him. It never bothers me to put away or throw away three month’s work. I’d rather have that down the drain than spend another six months on a movie that I know is not going to be successful.

“And with the TV show,” he added. “the networks are the ones who condemned it. I now have control over any new projects and I don’t want television unless they can come to me and say, ‘Okay, we’re going to have a series starring actors as good as Jack Klugman and Tony Randall.’ They come to you with some of the worst people in the world. MASH is so good, because they have Alan Alda and those people; and Archie Bunker has lasted so long because Carroll O’Connor is a first-rate actor. They get some of these kids with no experience at all, because they can save money. I won’t do Three’s Company with Suzanne Somers, who can’t act her way out of her hair. I’m just not interested.”

Eventually the subject shifted to TV shows that were based on his work, most notably 1970’s Barefoot in the Park (from the 1963 play and 1967 film starring Robert Redford and Jane Fonda of the same name), about a couple during the first year of marriage; and The Odd Couple, neither of which he made a dime off of due to a major oversight when the stage rights were sold to Paramount Pictures by his team.

“The Odd Couple took me a while to get to watch, because it was so close to me and I thought, ‘Oh, God, they’ve stolen by baby,’” Neil detailed. “But then people began telling me how good it was. I still never watched it until it was in reruns. One afternoon I turned it on and I found myself laughing. Since then I think I’ve seen 30 or 40 episodes. Barefoot wouldn’t make a good series, because it doesn’t have a continuing conflict. The Odd Couple is the perfect thing, because every week you know Felix is going to be annoying or Oscar will do something sloppy. In Barefoot, once you get over the initial impact of their marriage, they just go on with their lives.”

Which is about the time that Neil Simon wanted to go on with his life, but before the conversation ended, I wondered how many hours a week he spent writing. The response was one that pretty much any writer could identify with.

“Three or four hours a day for five days,” he replied. “After much more than that, you can practically feel all the electricity leaving your body. I have literally felt waves of energy leaving me, and it’s like you have to stop and come down from it. I sometimes get so hooked on it, that when I know I have to go to the bathroom, I won’t, because I don’t want to lose the thought I’m working on. It’s a very interesting process. It’s like I get up on a high diving board in the morning and say it’s too chilly and I don’t want to go in the water. You know, it’s such a long jump… but I jump anyway. When I’m in the water, I find that it’s warmer than I thought. People say, ‘Come on out,’ and I say, ‘No, I don’t want to.’ The minute I get in, it’s like turning on the electric typewriter, and then I don’t want to come out. But when I do come out, it’s hard to go back in again.”

Before we shook hands goodbye, I asked him to sign a copy of his Odd Couple script, which had been published in book form. He first looked at the author photo on the back cover and commented, “That doesn’t even look like me. It looks like my brother.” Then he opened the front cover to sign the title page and commented, “I can’t sign this. It’s a library book” (it was).

“Yeah,” I quipped, “but it’s an old library book.”

He signed his name and laughed with a shrug.

That’s right, I made Neil Simon laugh. Glad I could ever-so-briefly return the favor.