George Brich/AP/Shutterstock

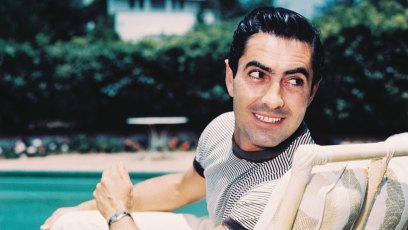

Cary Grant Was ‘Too Selfish’ to Become a Dad Early On: Inside Fatherhood Journey at Age 62

Cary Grant rarely had trouble talking to women, but he sent actress Merle Oberon over to invite the young woman he’d just seen perform in London to join them for dinner. Betsy Drake sat with the stars at the captain’s table that night in 1947, and by the time the Queen Mary docked in New York, she and Cary were in love.

Their marriage would last only 13 years, but Betsy would have a profound impact on the legendary actor. “I am close to happiness,” Cary gushed in 1959. “I wanted to rid myself of all my hypocrisies. I wanted to work through the events of my childhood, my relationship with my parents and my former wives.”

A daughter of the family that built Chicago’s posh Drake and Blackstone hotels, Betsy grew up shuffling between relatives after her jet-set parents lost their money in the stock market crash. She began acting as a way of curing her stutter and was starring in Deep Are the Roots in London’s West End when Cary saw her from the audience.

Despite a 19-year age gap — she was 24 and he was 43 when they met — they were both bright and curious. Betsy read voraciously and taught herself photography. Cary, who had been born Archibald Leach, created his cultured demeanor through self-education. But his suave manner only masked the insecurity he still felt over growing up poor with an alcoholic father and a mother who ran off when he was 10. It would be almost two decades before Cary learned the truth: His father had committed his mother against her will to a mental institution.

Betsy and Cary wed on Christmas Day 1949, with his friend, billionaire Howard Hughes, as their best man. Betsy soon learned that life with Cary could be trying. “The early loss of his mother made it hard for him to have a committed, trusting, stable relationship,” says Mark Glancy, author of Becoming Cary Grant. “Once they were married, he became very suspicious, distrustful and insecure.”

Betsy tried to alleviate his fears. She cooked, read him poetry over breakfast and studied hypnosis to help them both quit smoking. Though she received great reviews for their 1948 movie, Every Girl Should Be Married, she only worked sporadically. “Cary swallowed my life,” she said. “I lost myself in trying to please him.”

She briefly convinced Cary to slow down, too, so that they could enjoy their homes in Beverly Hills and Palm Springs, but he was restless. Betsy was even less successful getting him interested in starting a family. “He often said that he would have been too selfish to become a father [earlier in his life],” Cary’s last wife, Barbara Grant, tells Closer.

In 1956, Betsy arrived in Spain to the set of The Pride and the Passion and quickly realized her husband was having an affair with his costar Sophia Loren. “By his own account, he fell madly in love with her and wanted to marry her,” says Glancy.

Humiliated, Betsy left, booking passage on the Andrea Doria. On July 25, her ship collided with another ocean liner in heavy fog off Nantucket. Betsy survived, although dozens were killed.

The near-death experience and Cary’s infidelity sent Betsy into a tailspin. Things grew worse when her husband informed her that Sophia would be starring with him in Houseboat, a romantic comedy Betsy had written. “If I had any self-respect, I would have kicked him in the teeth and walked out,” Betsy said. She “simply stopped functioning,” her friend, actress Rosalind Russell, recalled.

Betsy sought help in therapy, including LSD treatment, which was legal at the time and being used as a way of dealing with trauma. She persuaded Cary to try the treatment to help him with his unresolved feelings about his childhood. He became an enthusiastic convert, crowing, “I never understood myself. How could I have hoped to understand anyone else?”

It was too late to save their marriage though. “One morning in bed while we were both having breakfast, Cary asked me a question and I said, ‘Go [screw] yourself,’” Betsy recalled. “That was the true beginning of the end.”

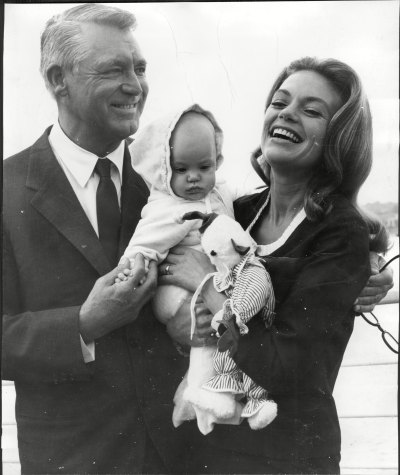

Cary’s next marriage, to actress Dyan Cannon, only lasted two years, but the effort he made to address his past gave him the courage to finally become a father. His only child, Jennifer Grant, whom he adored, was born in 1966. “He made his last film before she was born,” says Glancy. “He stayed home, saw her as often as possible and really enjoyed her childhood.”

Betsy went on to publish a novel and earn a master’s of education in psychology from Harvard. She never remarried and lived to be 92. She and Cary also remained friendly until his death in 1986. “I never clearly resolved why Betsy and I parted,” Cary said. “As far as one marriage can be compared with any other, ours was comparatively happier than most.”

— By Louise A. Barile

For more on this story, pick up the latest issue of Closer magazine, on newsstands now.