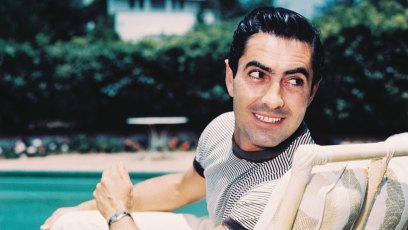

Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock

Andy Griffith Was Affected on a ‘Very Deep Level’ by Son’s Death, Daughter Says

Even after he became a huge TV star, Andy Griffith liked to spend his summers in North Carolina without shoes. “He would go into stores barefoot — sometimes even without a shirt!” his daughter, Dixie Griffith, tells Closer. “He wasn’t a typical Hollywood type.”

Growing up in blue-collar Mount Airy, Andy would never have dared dream of a home as beautiful as his 70-acre estate on Roanoke Island in the Outer Banks but returning to his native state every summer still helped him recall his roots. “That’s where he felt free,” Dixie says. “We would go on boat trips, play volleyball and go waterskiing. He loved to entertain and was pretty much the life of the party.”

Entertaining started off as a survival skill that Andy, an only child, learned in his youth. “His father was a foreman in a furniture factory, so his parents could dress Andy well. That worked against him because a lot of the kids from the poor side of Mount Airy were not clean or well dressed, and Andy got bullied a lot as a kid,” says Daniel de Visé, author of Andy & Don: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic American TV Show. Andy hit a major turning point in his life when he discovered that he could deflect bullies’ anger by making them laugh.

He took drama at Mount Airy High School and learned to play music — a talent that Andy would hone throughout his life. “He was very, very into music. He had guitars, banjos, horns and a piano,” Dixie reveals. “He could play pretty much any instrument.” Andy’s album I Love to Tell the Story: 25 Timeless Hymns even won a Grammy Award in 1997.

On his way to earning a degree in music from the University of North Carolina, Andy briefly considered becoming a preacher. Faith would always play an important part in his life, especially in troubled times. “I firmly believe that in every situation, no matter how difficult, God extends grace greater than the hardship and strength and peace of mind that can lead us to a place higher than where we were before,” Andy said.

In college, he acted with the Carolina Playmakers and started to write his own material. “He always urged me to write screenplays and scripts,” his Matlock co-star Nancy Stafford tells Closer. “He knew that it was a place where you could exert more creative control.”

Andy’s writing opened the door to a show business career. His comic monologue What It Was, Was Football, in which he played a country bumpkin trying to explain the sport became a national hit in 1953. The recording paved the way for Andy to star in the teleplay No Time for Sergeants in 1955 — a role he would reprise in the movie.

Over the next few years, he’d try his hand at radio and more films, including his villainous turn in 1957’s A Face in the Crowd, but after a producer saw him on Broadway in Destry Rides Again, Andy was offered his own TV series.

The Andy Griffith Show originated in an episode of The Danny Thomas Show in which Sheriff Taylor arrests Danny for running a stop sign. The spinoff series, about a widower raising his young son, Opie, in Mayberry, N.C., debuted on Oct. 2, 1960, and would run for eight seasons.

As Andy’s star rose, his personal troubles mounted. He had married Barbara Edwards, a fellow performer, in 1949. They adopted two children, Andy Samuel Griffith Jr., known as Sam, in 1957, and daughter Dixie, a year later. “I thought he was an absolutely great dad,” says Dixie, who says Andy always found time to play with her and her brother.

Andy loved fatherhood, but his marriage became unhappy. “They would stay married for another 10 years, but Andy had other relationships, and he and Barbara fought a lot,” says de Visé, who admits that as a husband, “Andy could be a handful.” Both drank too much, setting off more arguments. The marriage finally ended in 1972 when Sam and Dixie were teenagers.

Later on, Andy might have wondered what effect the divorce had on his son. Sam spent many years in trouble with the law before he died of alcoholism in 1996 at age 38. He and his famous father, who had paid for his rehab twice, were estranged at the time of Sam’s death. “My brother had some troubles, but it wasn’t my dad’s fault,” says Dixie. “ [Sam’s passing] affected him on a very deep level.”

Because of the publicity surrounding Sam’s death, Andy, who had just wrapped up nine seasons on Matlock, didn’t attend the funeral. It was not surprising — Andy hated speculation about his private life. “He thought there would be too many people there, too many magazines and cameras,” says Dixie. Sam’s death would remain a great sorrow, although Andy declined to talk about it publicly. Only his faith, the love of his third wife, Cindi Knight, and his family helped him survive it.

Andy, the person, would never be as perfect as the characters he embodied on TV, but he was proud to have created role models anyone could aspire to. Even himself. “He left us with characters that emulate the best of American values,” says Nancy. “Andy Taylor was a father, leader, a friend and neighbor. Ben Matlock was the defense attorney who would fight to the bitter end.”

In the years before he passed away in 2012 at age 86, Andy retired to North Carolina to spend time with Cindi and tend his garden. “Andy was not a public person,” costar Jim Nabors told Closer. “He loved doing the work, but he didn’t like getting out in public. He handled fame his own way.”

— By Louise A. Barile

For more on this story, pick up the latest issue of Closer magazine, on newsstands now.