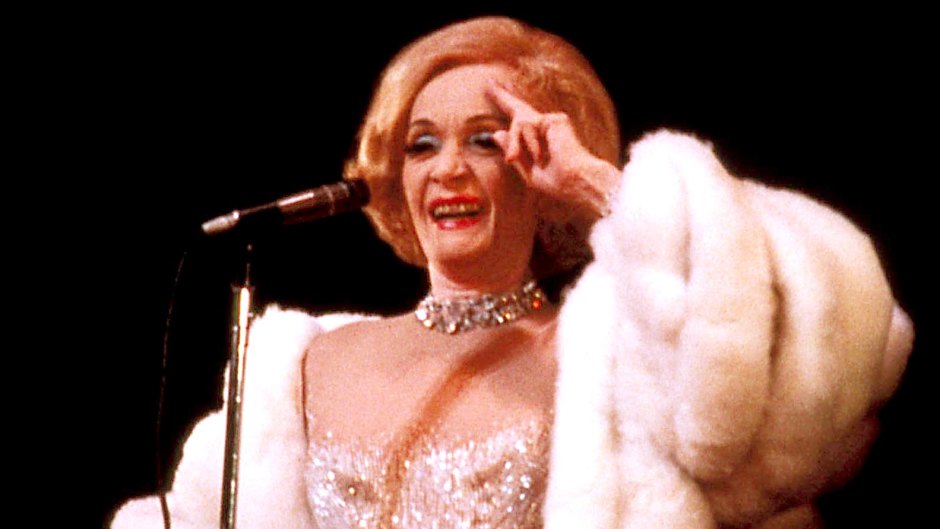

Globe Photos/Mediapunch/Shutterstock

Marlene Dietrich’s Grandson Peter Riva Recalls His Relationship With the Late Actress: ‘She Was Polite’

When the phone rang for Marlene Dietrich, her grandsons knew to behave themselves. “My grandmother would be in the house, making dinner or helping out. When the phone rang, we knew not to call her ‘Massy’ — which was our family nickname for her. She would instantly become Dietrich … Her body, her physique would change when she answered the phone,” Peter Riva tells Closer Weekly exclusively, on newsstands now.

The Berlin-born performer, whose glamorous image helped her to become one of the highest-paid actresses of the 1930s, always tried to set a good example for her grandsons. “If you were sick, she’d be the first one to make soup and find out if you’re okay,” he says. “But she never patronized anyone. It was part of her ethic. She never tried to be superior to anyone, but she tried to show by example how you could be better.”

Born into an aristocratic family, Marlene was a product of the enlightened Weimar culture that thrived in Berlin before World War II. “That was critical to understanding who she was,” Riva explains. “When anybody starts discriminating against another person, be it for race, color or religious belief, that was an anathema to her.” Marlene’s teenage dreams of playing violin were dashed by an injury, so she became active in the era’s vaudeville-style theater where she embraced new freedoms. “All the young available men had been killed [in World War I], so she’d dance with women,” Riva says. “Sometimes she’d dress as a man, sometimes a woman. There was an androgyny built into what was needed for entertainment at the time.”

In 1930, Marlene revisited her Berlin years by cross-dressing in a men’s tuxedo in her first American film, Morocco, which caused a sensation. By then, she was on her way to becoming an international star — one that the Nazi party wanted on its side. “She was offered to virtually become the queen of Germany,” says Riva. “She was polite. But the moment she could oppose them, she did by becoming an American citizen in 1939.”

Marlene immigrated to America with her husband, Rudolf Sieber, an assistant director and the father of their daughter, Maria. The pair, who wed in 1923, remained married until his death in 1976, even though they were unfaithful to each other. Marlene was rumored to have had affairs with Hollywood stars including Gary Cooper, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., James Stewart and Yul Brynner, but her grandson notes that lasting love eluded her. “My grandmother could fall in love 10 times a day with a song, a beautiful flower, a man, a woman — she would have romantic schoolgirl crushes,” he says. “But I think the turmoil of her times removed her from the ability to really know what love was.”

That was also the case in her relationship with her daughter, Maria. “[Marlene] really didn’t understand how to love her own daughter,” says Riva, who explains that his grandmother’s means of communication, while “not unkind,” could be “authoritarian.” Even so, “the love of her life was my mother.”

Marlene retired from public life in 1975, after she broke her leg while performing. “Whenever we’d go through Paris, we’d stop in and see her,” says Riva, who explains that his grandmother took her image so seriously that she ended her career to avoid disappointing her fans. “The last years of her life were busy, but just not busy in public,” he explains. “She had a simple one-bedroom apartment in Paris with a lovely balcony with geraniums on it. She’d respond to 150 fan letters a week. She wasn’t a recluse in any sense of the word, but she felt she had [a] duty to the pleasure of others.”

Louise A. Barile, with reporting by Fortune Benatar

For more on David, pick up the latest issue of Closer magazine, on newsstands now.