Shutterstock

How Louis Armstrong Overcame a Tough Childhood to Become One of the World’s Most Influential Musicians

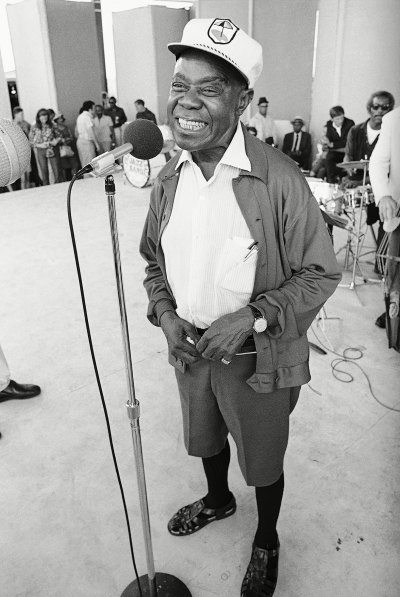

To the world, he was “Pops” or “Satchmo,” the most beloved jazz musician in history. But to kids in his modest New York neighborhood, Louis Armstrong was family. “We’d shout, ‘Uncle Louis is home!’” Denise Pease, 67, tells Closer Weekly exclusively, in the magazine’s latest issue. “He gave us 50-cent pieces to save for college, but we’d go get candy.”

With a charismatic, upbeat personality and expert musicianship, Louis helped take jazz mainstream while bridging the gap between white and black cultures at a time of hostility and segregation. “He never wanted a lot of money or a big house or a lot of possessions because he figured out early on what was important in life,” says Ricky Riccardi, director of research collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum. “He always exuded love — on and offstage. He would say, ‘I just want everyone to love everyone.’”

Growing up desperately poor in New Orleans was an education in survival. “Louis’ father abandoned him, and his mother had health issues, so he lived with his grandmother in a part of New Orleans nicknamed The Battlefield — there were murders and gunfights every day,” Riccardi says. To help feed his family, little Louis sometimes resorted to digging through trash.

On New Year’s Eve 1912, fate intervened. Louis, then 11, picked up his stepfather’s gun and shot it into the air in celebration. The police detained him and he was sent to The Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, where Louis picked up his first musical instrument, the cornet. “Detention gave Louis structure and a great music program,” says Riccardi, noting that within six months of his release, Louis began playing with a brass band.

A Wonderful World

What followed was the making of an icon. Louis, who switched to trumpet, learned to perform New Orleans traditional music during second-line parades and at dance halls and on riverboats. Eventually, he graduated to big bands, touring the country as he developed his distinctive gravelly voice and scat singing. “Louis created the language of jazz as a form of musical speech,” Dan Morgenstern, a longtime friend, tells Closer.

As he became more successful, Louis began breaking racial boundaries. “He became the first African-American to insist that he wouldn’t play music at a hotel unless he could sleep there. He also was the first to have a nationally sponsored radio show,” Riccardi notes. For 30 years, Louis performed as many as 300 performances a year and helped make American jazz popular around the world.

Yet by the 1950s, as the civil rights movement ignited, some in the black community mistook Louis’ smiles and message of love as acceptance of oppression. “This kind of stuff hurt him until the day he died,” says Riccardi. “He never wanted to be white, everything he did was unapologetically black.”

Louis finally took a public stand after the 1957 Little Rock Crisis, where nine black students were prevented from entering a racially segregated school.

“This really angered him,” says Riccardi. During an interview, Louis called out President Eisenhower over the incident and related his own bitter experiences touring the segregated South. “It was one of the defining moments of his career,” says Riccardi. “He was the most popular African-American performer and he dared to tell off the government. Now, almost 50 years after he’s gone, he’s viewed as a civil rights pioneer.”

Louis, however, was happiest playing music or sitting on the front porch of his little house in Corona, N.Y., where he lived with his wife, Lucille, from 1943 until his death in 1971. “His manager tried to talk Louis into moving into a really nice house on Long Island. He felt that where he lived wasn’t good enough for a big star,” remembers Morgenstern. “Louis absolutely refused. He said, ‘This is my neighborhood. I’m not going anywhere.’”

For more on this story, pick up the latest issue of Closer Weekly, on newsstands now!