Paramount Pictures (2); 20th Century Fox

Go Behind the Scenes of the Great ‘70s Movie Musicals: Barbra Streisand to ‘Rocky Horror,’ ‘Grease’ and More

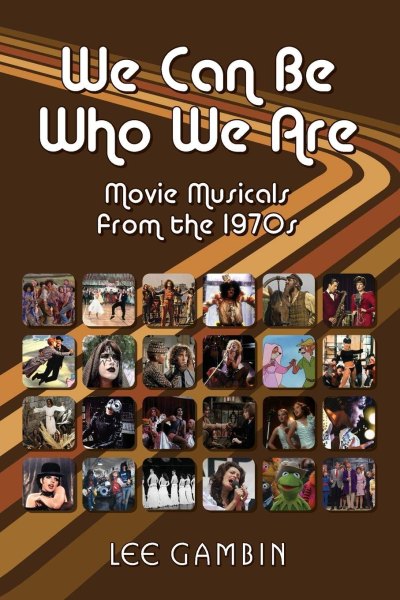

Movie musicals have been a part of Hollywood from the beginning, capturing the imagination of moviegoers generation after generation, and they’re still going strong — proven by the success of films like Hugh Jackman’s The Greatest Showman and Disney‘s Beauty and the Beast. One of those moviegoers is journalist and author Lee Gambin, who wrote the book We Can Be Who We Are: Movie Musicals from the ’70s.

“I come from a history of loving all film types, but if you look at the trajectory of my career, it started with horror,” Lee explains in an exclusive interview. “I wrote for Fangoria magazine and then on to different periodicals and websites that focused on that genre. But in going through my love of certain genres, I realized that horror seems to have been misrepresented by people who think that it’s one very specific thing. I’ve always felt the same with musicals; that people didn’t realize musicals could be incredibly versatile and diverse, so I wanted to champion that.”

In considering the best way to do so, he decided to write a book about movie musicals of the 1970s. “A lot of films from that period were underrepresented and under-discussed,” he says. “I’m sure everyone knows everything about Grease and The Rocky Horror Picture Show, but there were so many others people were missing out on. Also, films like Hello Dolly! and Doctor Doolittle got roped into this notion that musicals were falling out of favor with the audience’s needs, but they failed to realize that at the same time films like Oliver! were not. They were really successful, so the idea of championing the musical as something that wasn’t falling out of fashion was my goal.”

It would seem he achieved it. In what follows, Lee provides behind the scenes information on a number of musicals released between 1970 and 1980, many of which were enormously successful.

Please scroll down for more.

Be sure to check out and subscribe to our Classic TV & Film Podcast for interviews with your favorite stars!

1 of 18

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

‘On a Clear Day You Can See Forever’ (1970)

As Lee explains it, “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever is a really rich, beautiful, amazing film that captures the turning point of the ’60s into the ’70s. The concept of the musical is remarkable: Barbra Streisand plays a chain-smoking student who wants to stop smoking, so she sees a shrink who hypnotizes her to stop smoking and ends up channeling her past lives. What happens is he falls in love with one of her past lives, but can’t stand her current one. He’s actually annoyed by her current one.

“What I love about the film,” he notes, “is the artistic vision of [director] Vincente Minnelli in terms of how he presents the past lives and marries them with the contemporary world. All of Streisand’s costumes very stylized, and so is the look of the film itself. The songs are terrific and very different to the stage show, so there’s that translation to the screen that makes it very different. I did find out that Jack Nicholson, who plays her stepbrother, had a number that was cut. They felt it wasn’t moving anything forward, and there was some concern about his singing voice.”

2 of 18

Paramount Pictures

He notes, “I feel it’s my favorite Streisand performance, because she plays neurotic really well. The patter of her talking is endless and it’s really kind of endearing. And so is the character of Daisy Gamble, who is just perplexed by these past lives. And her vocal talent is nothing short of a marvel. You can’t deny her vocal talents regardless of what you think of Streisand as a performer, an entity, what she represents and who she is.

“There’s a really beautiful still that I was lucky enough to get for the book, which has Vincente Minnelli directing Streisand, and the way she is watching him and taking everything in, you can tell this is someone who is a master of her craft, learning from another master. I believe that On a Clear Day You Can See Forever helped move her into directing herself as she becomes one of the big names in filmmaking from the ’70s into the early ’80s. Not just as a woman, but as a filmmaker herself.”

3 of 18

R/R

‘Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory’ (1971)

“Where do you you begin?” Lee laughs. “It’s an opus; a really big, spectacle film, but it has this gritty opening. A documentary feel to the opening with the kids finding the Golden Tickets, media coverage being kind of a storytelling device, and then you enter the world of the Chocolate Factory and it just shifts and changes. But what it does beautifully is keep the songs happening during the opening, so you’ve got songs like ‘Cheer Up, Charlie,’ ‘Candy Man’ and ‘I’ve Got a Golden Ticket.’ All of that serves as a reminder that you’re in a musical, so get used to it, because people aren’t going to only start singing when we get to the fantasy world. That’s very different to, say, something like the Ross Hunter production of Lost Horizon, where there are no songs until we get to Shangri-La, which is a bit of a let down.

“Joel Gray, who was initially intended to play Willy Wonka, would have been terrific, but I just loved Gene Wilder,” he notes. “I can’t see anyone else in that role. He’s so creepy, it’s unsettling. I remember seeing it as a kid and thinking of it as a creepy film. The moral judgments are dicey, the Oompa-Loompas are sort of a moral guard, but they’re letting these kids perish. It’s a really interesting film and kind of a response to the recession that’s happening. And it’s a universal film in that it’s all about the different nationalities and races and class divisions. The idea of Charlie inheriting the Chocolate Factory comes at a lot of costs to him personally, spiritually and philosophically. He’s got to relearn about life. So the growth of Charlie arc is rich and dark and complex; it’s not a simple thing. It’s very similar to Dorothy’s growth in The Wizard of Oz. He asks questions, he fumbles in the dark, he makes mistakes, which is very interesting.”

4 of 18

Getty Images

The other thing he points to, naturally, is the music by Leslie Bricusse. They are just beautiful, gorgeous songs. I think there’s something ridiculously menacing throughout the whole fabric of the film, but the music is something that sets it apart from a non-musical child-centric film of the same period. There’s something about Wonka singing ‘Pure Imagination’ that is whimsical and sweet and promising, but also with this underlying sort of menace and darkness. The idea that imagination can actually destroy. Wonka is there to create and also to destroy and I like that about him. He’s not a clean-cut messiah. He’s someone a little bit dodgy. Also, turning Roald Dahl‘s novel into a film really helps that element. If it was a straight piece, you probably wouldn’t get it. With the songs there’s this false promise, which is really interesting. As a result, it’s a musical that’s very much subversive with the idea of promise, but an underlying cost.”

5 of 18

Allied Artists /Hulton Archive/Getty Images

‘Cabaret’ (1972)

“This is one film who people say — and I say stupidly — ‘I don’t like musicals, but I do like Cabaret.’ There are a few movies like that; Gypsy comes to mind. Again, like Wonka, it’s a masterpiece. That word gets thrown around a lot, but it’s definitely the case for Cabaret. It’s terrifying, unsettling, smart and grim and bleak, and gives you this razzle-dazzle that is a lie. The emcee as played by Joel Grey is just as evil as Hitler. When I talked to him, he said he played it just as evil as Hitler. He’s welcoming people in his cabaret, into his Kit-Kat club, but is giving them this monstrous expression of how they should feel about themselves, the idea of the rise of Naziism sort of counter-playing what he’s suggesting in his songs and what he presents.”

“Liza Minnelli‘s performance is outstanding. Just an incredibly gifted artist who does this wonderful work. This performance is hers. Like Wonka with Gene Wilder, you can’t imagine somebody else doing Sally Bowles. And the idea that Bob Fosse had all the songs introduced at the Kit-Kat club was a really smart choice. The one song he leaves outside of the Kit-Kat Club is ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Me,’ which is sung by the Nazi youth and is the most unsettling, evil song, because it’s a promise of happiness and good health and the beauty of nature. All this wonderful stuff, but it’s really about Nazism. So it’s really scary. And that great image of all the Nazis rising and the people who are questioning it or conflicted by this regime stay seated and look miserable. That reflects into the last image of the film, which is unsettling where the Kit-Kat Club is now ruled by Nazis wearing their swastikas proudly. And we fear for these characters who loved Sally Bowles, because they’re going to be dead, they’re going to be gassed. There’s no question of it. There’s no room for these Bohemian artists; they’re perceived just as evil and sinister as the Jews or the gays.”

“Just amazing stuff. The songs are just ridiculously incredible, and what I love about the film specially is Sally as a character is supposed to be not that great a performer. And she likes living through the Kit-Kat Club. That’s how she exists and I love that aspect to her. The film deals with all this really heavy stuff. I remember it being one of the first things I saw a child where abortion was brought up, and this sort of ghoulishness of the cabaret and the way the dancers were all made up. It just hypnotized me. Just a dark, rich nightmare of a film and it’s just fascinating to watch.”

6 of 18

Universal/Getty Images

‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ (1973)

Lee comments of this Broadway musical turned movie, “I interviewed [director] Norman Jewison regarding Jesus Christ Superstar as well as Fiddler on the Roof. I think Fiddler on the Roof is a masterpiece as well. The perfect film about the fear of change, which summarizes youth culture as well even though it’s set at turn of the century Russia. Then he and I moved on to Jesus Christ Superstar and he pointed out that they are two very different musicals. It’s a superb film. The perfect, most innovative way to adapt this rock opera, which really could have gone any which way or direction. You could have done it as a classical piece looking exactly like the time of Christ, or you could have completely updated it and set it on the streets of L.A. They didn’t. They did a hybrid with scaffolding in the desert in Tel Aviv, and a bunch of young rock and roll types who were doing this sort of play out in the desert. Then there’s a mystical element, because Christ dies, but doesn’t resurrect and they leave Ted Neeley [who played Jesus] and go back on the bus. So it was like this elaborate suicide in a sense. He’s just dead, which made it controversial as well. There’s a fantastic score by Andrew Lloyd Webber, but orchestrated by Andrew Previn, who just breathes brand new life into it.

7 of 18

GAB Archive/Redferns

“One of my favorite things in talking to Norman Jewison was the discussion of my own critical thoughts of Superstar,” he says, “and what it sort of says as a commentary on the recording industry. I said to him, ‘I’ve always seen this version of Jesus as the first rockstar, Mary Magdalene’s his number one groupie and Judas is his concerned manager.’ He got that, which is cool, because sometimes you don’t want to push your own critical thoughts on filmmakers, but he was really open to it. He told me great stories about the guys from Deep Purple and Black Sabbath working along with the London Symphony Orchestra and how that was so different. They all had to merge together to make this score.”

8 of 18

20th Century Fox/Archive Photos/Getty Images

‘Phantom of the Paradise’ (1974)

For Lee, one of the most intriguing aspects of movie musicals from the 1970s are the directors who “crossed over,” so to speak, to make musicals, who you would never otherwise have expected to do so. Phantom of the Paradise, a rock and roll take on Phantom of the Opera, was one of them. “There were a wave of filmmakers like Norman Jewison, Martin Scorsese and, in this case, someone like Brian De Palma, who comes in and does this incredible take on the Phantom mythology, but sets it in the world of rock and roll. And all of these film devices were used so well, like split screen, the sort of bombastic colors and color schemes; the incredible music by Paul Williams. This is another musical that ‘non-musical’ fans love.

“Brian De Palma is obviously a massive fan of classic musicals, because there’s a lot of influence in there. You can see Busby Berkeley, you can see all the stuff from Arthur Freed — these filmmakers of great musicals from the Golden Age are in this rock and roll horror musical. There’s the influence of Faust in there, and it’s just a really cool, great and loud rock and roll film that transcends what you can do with hybrid film genres. What’s amazing is how much Paul Williams did during this period — Bugsy Malone, The Muppet Movie, this, A Star is Born.”

9 of 18

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

‘The Rocky Horror Picture Show’ (1975)

A newly engaged couple (Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon) break down in an isolated area and must pay a call to the bizarre residence of Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry). “Definitely a cult classic,” points out Lee. “In my writing on it, I sort of discussed the magpie’s nest that it is, and how it’s [writer] Richard O’Brien just basically grabbing everything he loved as a kid and chucking it into one thing. As an adult, and someone who is now a pop-culture vulture, you watch and go, ‘This is a perfect marriage; a perfect union of all these great elements.’ You’ve got the romance comics of the ’60s, you’ve got horror movies, you’ve got slasher movies, you’ve got science-fiction, you’ve obviously got musicals and the whole muscle culture.’ And it’s just presented so wonderfully and it’s all about the whole message of don’t dream it, be it.

“And it comes out during the whole sexual liberation movement, you’ve got the women’s movement, the gay liberation front, you’ve got punk, you’ve got glam rock. You have all of this stuff happening, and it’s a perfect response to it all. And what I love about it as well is that it doesn’t play as clean-cut, ‘Oh, just be happy with who you are and you’ll be fine,’ because by the end of it Janet and Brad are destroyed. They are walking through rubble and there’s no happy ending. The conservatives who were pretending not to be conservative win, right? So, again, it’s a political statement. It’s the whole idea of don’t dream it, be it — but be it to a point. This explosion of the celebration of rock and roll and punk and sex and sexual liberty and all this stuff comes at a cost in this story. If you look at the history of a lot of these musicals, they have very dark endings. Fiddler on the Roof has the Jews exiled from Russia, Cabaret has the rise of Nazism, La Mancha is the Spanish Inquisition. These are things that happen where characters aren’t completely going to be strolling hand in hand all cheery and happy like Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland in those excellent Arthur Freed [or] Busby Berkeley musicals. So while it gets championed as a celebratory thing, people forget the element that Janet and Brad end up destroyed by the sexual freedom they’ve experienced for the last hour and a half.”

10 of 18

Columbia Tristar/Getty Images

‘Tommy’ (1975)

Added into the directorial mix of musicals in the ’70s is Tommy‘s Ken Russell, whose other credits include The Devils and Altered States. Enthuses Lee, “Like Jesus Christ Superstar, it’s a perfect way to do a concept album that was not yet a stage show. So Tommy went from concept album from The Who to this film and it’s just perfect. The cast they assembled and the way they present this rock opera about this kid who’s traumatized and then becomes this messiah to alienated, disenfranchised youth — inadvertently and via playing pinball of all things— is amazing. This wacky concept is presented so vividly strong and powerful and is this wonderful commentary on the hypocrisy of religion, healing, the role of the media, greed and corruption.

“All of this and that score by The Who — it’s just outstanding. On top of that, there’s Ann-Margret‘s dazzling performance as Nora, which is just out of this world. As much as I love Louise Fletcher in Cuckoo’s Nest, I really feel Ann-Margret should have taken home that Oscar. You can’t compare the performances; they’re too bloody different.”

11 of 18

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

‘Bugsy Malone’ (1976)

Imagine a James Cagney gangster movie from the ’30s, and you’ll get the set-up of this musical fantasy, only the gangsters are kids (Happy Days’ Scott Baio and Jodie Foster among them), whose musical vocals are dubbed in, they’re armed with pie-firing tommy-guns, and they drive their cars by peddling.

“I view Bugsy Malone as a kid version of Pennies From Heaven, which is very dark,” muses Lee. “That film has rape and murder, abortion and prostitution in it, and you don’t get that, obviously, from Bugsy Malone. But this whole thing of lip-syncing to songs makes it otherworldly. I think [director] Alan Parker is a genius. What he does with Fame is just incredible, what he does with horror films with Angel Heart is amazing. He does diverse films, and he does Bugsy Malone, which is just incredible because it’s this stylized tribute and throwback to ’30s gangster movies, but it’s still just as dark and as bleak as those movies. The ending is fun — the kids gunning each other down with pies is cool — and the message is that you create who you are and you can be who you want to be. It’s nice to see that in an the realm of a decade that was all about characters losing themselves to the road taken, which wasn’t the right road to take in the first place. But with Bugsy Malone, the whole premise is you can create who you want to be.

“Jodie Foster is a knockout in this film; her performance is amazing and you can see the wisdom beyond her years in it. She shot Taxi Driver before this, so for her to come from that and into a film with a bunch of kids, was a big jump.”

12 of 18

Getty Images

‘A Star is Born’ (1976)

When many people think of A Star is Born, undoubtedly images of the Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga film come to mind, but that was actually the fourth take on this particular story. The third was released in 1976 and stars Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson.

Lee points out, “Streisand is at the top of her game and that voice is a marvel, and Kris Kristofferson’s performance is so good. This film comes out in a period of the sensitive, real men kind of syndrome that was happening, so you have all these really sort of tough dudes — real men’s men — but they’re also men that kind of sacrifice for women. There’s a whole slew of movies; you get Westerns like this, you get The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing, with Burt Reynolds who basically does everything he can for Sarah Miles, and then you have Kristofferson, again, in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and he sacrifices his own life for her to have happiness. So these are are men who are real manly, but also look after women and care for women and let the women grow. A Star is Born is a perfect example of that. He is on the decline, he is an alcoholic and a drug addict; he’s depressed, he’s bored. That’s the essential thing, but he’s constantly propping her up and looking after her. I love the Garland version, but this one, the stadium rock version, I do like as well. The problem with it is that it gets bogged down. You can see there were so many writers on it that sort of threw in their input. You can see that these sequences are bogged down and ignored in favor of montages, which do nothing for the film. They don’t tap into their relationship and how tumultuous it is.”

13 of 18

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

‘New York, New York’ (1977)

Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli play, respective, an egotistical saxophonist and a younger singer who meet on V-J Day and begin an oftentimes difficult relationship as they try to achieve their career goals. Martin Scorsese directs. “My favorite photo regarding this film is one of Scorsese at the Moviola, running through the film, and Liza Minelli’s there with him, and also over his shoulder his Vincente Minnelli. That image really sums up the movie,” Lee smiles. “It’s Martin Scorsese’s love letter to Minnelli, who was one of his idols and a master teacher. And Scorsese and Liza, their collaboration as artists is just remarkable. But New York, New York is so heavy and it breaks my heart every time. Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli … my God, the chemistry on screen is just palpable and scary. It’s violent, passionate and heated, and Scorsese balances the magic of the film and the gritty realism. So he has these artificial sets, but then he has really straight-up dialogue. The sequence that gets me all the time and I can’t actually watch it — it’s too confrontational — is the car scene where they’re arguing. It just goes on for ages and gets to this point where they’re just screaming at each other and it’s unsettling. That kind of stuff is really classic Scorsese; he just gets in there and makes you feel uncomfortable. And then, juxtaposed to that is all this beautiful celebratory stuff that pays tribute to classic Hollywood. I really wish Scorsese would make another musical.”

14 of 18

Paramount/Getty Images

‘Saturday Night Fever’ (1977)

Admittedly this one might be a surprising one to have on this list of musicals, but Lee absolutely believes it belongs. “Not a traditional musical,” he suggests, “but someone called it a ‘dancical.’ It does use music to move the story forward, and it uses it as an expressive tool in a diegetic way, but also to comment on character. So the character that John Travolta plays is one who comes to life through music. He’s in a dead-end job, he’s an immigrant kid, he’s a very poor, working class Italian guy, and then when he gets to the disco he’s king, right? The use of the Bee Gees and all of the other disco stuff in the film is used to push the story forward and to have an insight into character or to comment on the scenario.

“I love Saturday Night Fever for its brutal examination of masculinity. It really is about what it means to be a man, and this guy, Tony Manero, you love him and you hate him. He’s complicated and he’s explosive and he’s cool, but also really uncool. Everything about him is just really complicated and captivating. What’s interesting is that films like Saturday Night Fever and Fame, are these movies that are really dark, gritty, grimy films, but people don’t remember that. They just think, ‘Oh, yeah, it’s Travolta doing his dancing in the disco,’ or in Fame it’s just kids jumping around the taxis, dancing. But watch them again. They’re really brawling, gritty, hard films.”

15 of 18

Paramount Pictures/Fotos International/Getty Images

‘Grease’ (1978)

“This is one of those films where you either love it or you hate it,” Lee reflects of the John Travolta/Olivia Newton John musical adventure, “or people are sort of torn between liking it or not. But you can’t deny its importance, because it changed the way people thought about musicals. It’s a big box office hit, what critic Pauline Kael called a popcorn junk pile film, along with Star Wars, Superman … all the films that made lots of money that were really accessible and easy to take in and watch. I love that Grease is bittersweet and has a real sort of undercurrent of sadness. The ending, with ‘We Go Together’ being the heart of the story, really hits a nerve. It makes you sort of weep, because you don’t actually know where these kids end up. That’s the thing about Grease: these are dead-end kids. What the hell are they going to end up doing? If you look at other high school-themed musicals of earlier years, like in the ’50s, you kind of get a sense the kids are going to be alright, but with Grease you don’t really know.

“It’s also a film that really plays into the ’70s being obsessed with ’50s culture. There’s a lot of that happening at the time: American Graffiti, Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley. There are also elements of ’50s culture in things that are contemporary or fantastical, like Rocky Horror. Essentially the songs in Rocky Horror are very ’50s rock and role songs. And then Grease happens and it sort of says, ‘Rock ‘n’ roll is here to stay.’ You may have Saturday Night Fever, which is all about disco, but rock ‘n’ roll is king as far as storytelling goes. Rock ‘n’ Roll is the epitome of what ’70s musicals were about when you think of rock music influencing Broadway. It starts with things like Bye Bye Birdie, but really kind of catapults with things like Hair.”

16 of 18

Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images

‘The Wiz’ (1978)

“As far as I’m concerned,” says Lee, “The Wiz is one of the most insane stories in Hollywood history, but also one of the most political films, a really important black film and also one of the last ‘blaxploitation’ films in the purest sense of that era. It’s also a really bizarre, nightmarish take on a stage show that was pretty much a black version of The Wizard of Oz with a Motown score. But the way [director] Sidney Lumet presents it on film, he can’t not make it a political film or have something socially relevant to say.

“The idea of changing the Dorothy character to an adult school teacher who’s scared of life is really interesting,” he continues, “because it’s kind of talking about black women who were told they had to stay down and they’re oppressed all this time and now they get to grow and learn and experience life, which is really cool. Also, the ghetto and Harlem becoming Oz was really cool; all the tropes of black urban culture thrown in there that kind of respond to what is happening in Oz. You see as the film progresses and she’s moving forward, there’s lots of primal screaming that Diana Ross does and a lot of questioning her sense of worth and who she is and where she’s going to move to. Michael Jackson‘s Scarecrow is always philosophizing; he’s got these strands of his head stuffing made of different quotes from philosophers. The Tin Man not being able to feel. It’s all sort of black experiences embedded in this rock and roll, weird-looking musical with excellent designs by Stan Winston and Tony Walsh, who did the costumes. He was Julie Andrews‘ husband. Jeffrey Holder worked on it as well, as did Ted Ross and Nipsey Russell and Quincy Jones and Lena Horne … it was just a really weird combination of artists that resulted in an interesting, fascinating film.

“I do love the story that Diana Ross went to the studio and said, ‘You should make Dorothy an older woman and I want to play this role.’ Poor Stephanie Mills was out. But the casting does make it different; it makes the film more adult. As a result, there’s more room to explore darker territory.”

17 of 18

Tony Korody/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images

‘Hair’ (1979)

Claude Bukowski (John Hurt) arrives in New York from Oklahoma, where he finds himself embraced by a group of hippies led by Berger (Treat Williams). Conflict arises from the fact he’s been drafted to go to Vietnam and that he has fallen in love with the rich but rebellious Sheila Franklin (Beverly D’Angelo).

“The stage show of Hair is probably one of the most important musicals of that period, but also one of the most important pieces of American theater of all time,” Lee enthuses. “It’s revolutionary, it’s smart, it’s hard-hitting, it’s controversial, it does everything that working theater should do. When it came to the film adaptation, obviously when you’re doing a stage to film adaptation, you want to make it streamlined and have a plot that’s tangible that audiences can grab onto. The stage musical has a wafer-thin plot line. It’s pretty much expressionistic, is vigorously anti-war and anti-American with anti-American sentiments. It’s also anti-religion, angry and it feels very sexual. So it’s got all this stuff happening. The film was directed by Milos Forman, another master, who hires a screenwriter that writes a straight-lined plot and it changes a lot from the stage show. But it works okay.”

“The problem is that the songs don’t seem to hang off any kind of plot. Sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t, so you’re kind of watching this thing where it breaks into song and it’s a little bit jarring, because you’re following this very dense plot, which is very dramatic, and the songs are dramatic, but they don’t seem to tie in well. At the same time, it doesn’t really matter, because what you’ve got here as well is the incredible choreography from Twyla Tharp. Again, I love its moodiness and its anger, which I like because it is an angry musical.”

18 of 18

MGM

‘Fame’ (1980)

There are a lot of things that Lee admires about Fame, which explores the lives of teenagers attending a New York high school for the performing arts. “One of them,” he says, “is that the kids don’t get closure. You don’t know what happens to them, and that’s something that is chilling. If you watch the film, there’s the suggestion of rape with the Irene Cara character. The Ralph character, played by Barry Miller, is addled by drugs, but you never see him again. It’s a very honest and brutal film. It suggests that you may want to be in the arts, but it’s going to cost you. It’s in the tagline for the film itself, which is perfect: ‘If they’ve got what it takes, it’s going to take everything they’ve got.’ It’s just this whole idea of the arts consuming you and spitting you out. And they’re just at school. They’re not even in the industry yet.

“But I love its bleakness, its honesty, its ugliness, its grittiness. The way the kids are all sort of alienated. The frenetic brilliant editing. The songs are terrific, the way each character is sort of representative of a different ghetto or a different experience. That great moment with Anne Meara as the teacher when she screams at Leroy and says, ‘Don’t you kids ever think about anything but yourself?’ So it’s the idea that we love these kids, we want them to succeed, but they’re also pretty self-involved, just caring about their own dreams.”

Seemingly a perfect entry point into the 1980s.