Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

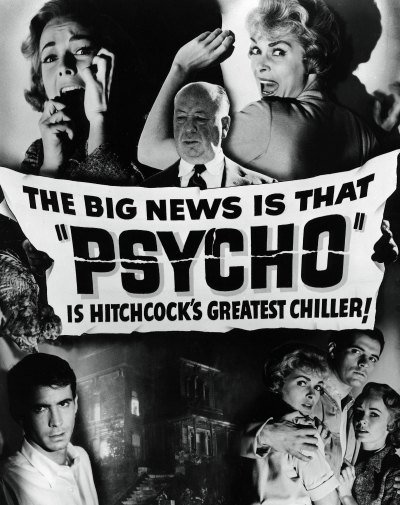

‘Psycho’ at 60: Behind the (Shower) Curtain with Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh, Hitchcock and ‘Mother’

You may be able to credit Jaws with chasing people out of the ocean, but Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock’s horror classic which is celebrating its 60th anniversary, actually scared the audience out of the shower. And who can blame them? Moviegoers in 1960 sat in shock as they watched Janet Leigh as Marion Crane check into the Bates Motel and enter a shower, only to find herself viciously attacked by someone wielding a kitchen knife and left for dead.

“I don’t think anybody picked up a knife and graphically did somebody in until Hitchcock got Janet Leigh in the shower,” reflects Tom Holland, writer of Psycho II and Fright Night. “I think that sort of set everybody’s mind working. They took it a lot further as time went on, God knows. The serial murders, the non-storyline murders, may have started with Halloween, but I don’t think the graphic killings would have been possible without Hitchcock opening up a whole new emotional level in Psycho.”

Psycho mastered the concept of the story misdirect. It starts off focusing on a woman who, to be with her lover, steals $40,000 from her boss. En route to meet John Gavin’s Sam Loomis, she has a change of heart and realizes she needs to return the money. A terrible rainstorm causes her to have to check into the aforementioned Bates Motel, where she encounters proprietor Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). They talk for a bit, she overhears a vicious argument between he and his mother in the nearby house on the hill, and tries to console him before saying goodnight. Not long after, Marion suffers her showery death, the implication being that the old lady did it, with Norman covering it up by sinking Marion and her car in the nearby swamp to hide the crime.

And this is where things shift. The movie suddenly becomes about the search for Marion, but, more importantly, the story of Norman Bates, who, it’s revealed (and, yes, there are spoilers here — but the movie is 60 years old), murdered his abusive mother decades earlier. The guilt of doing so created a split personality within him where one part of his brain is Norman, the other “Mother.” He has conversations with her, dresses as she would have to commit murders and has placed mom’s corpse in her bed — until he has to move it to the fruit cellar to avoid detection.

“The thing that appealed to me and made me decide to do the picture, was the suddenness of the murder in the shower, coming, as it were, out of the blue,” noted Hitchcock, whose credits up until that time included Rear Window, Vertigo and North by Northwest. “I didn’t start off to make an important movie. I thought I could have fun with this subject and this situation. It was an experiment in this sense: Could I make a feature film under the conditions of a television show? I used a complete television crew to shoot it very quickly. The only place where I digressed was when I slowed down the murder scene, the cleaning up scene other scenes that indicated anything that required time. The rest was handled the same way they do it in television.”

For much more on Psycho, please scroll down.

Everett/Shutterstock

Everett/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Ray Jones/Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

Courtesy Virginia Gregg

Courtesy Little A

Bryanston Distributing Company

Courtesy Little A

Everett/Shutterstock

Universal Pictures

Universal Pictures

Showtime

Universal/Kobal/Shutterstock

NBCUniversal