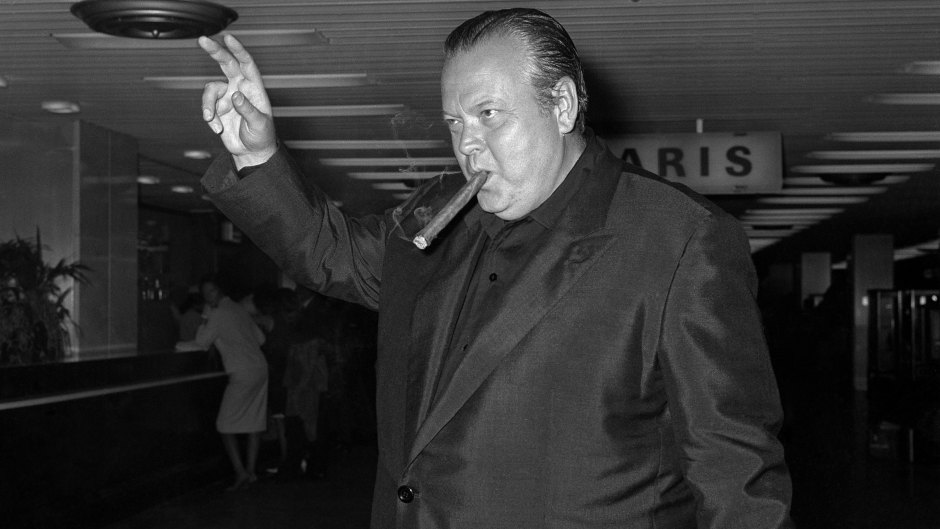

Levy/AP/Shutterstock

‘Citizen Kane’ Star Orson Welles Struggled to Maintain Relationships: Why He Was Divorced 3 Times

Orson Welles is a legend among legends. “If there were a Mount Rushmore of directors, he’d be one of the four faces,” Patrick McGilligan, author of Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane, tells Closer. But while his star shone bright, the lingering scars from Orson’s turbulent childhood dimmed the joy of his personal relationships. “His legacy is greatness — flawed greatness, but that’s what his movies are about, too,” McGilligan notes, citing how the icon’s work often reflected his complicated life.

Orson was born in 1915 in Kenosha, Wisconsin, to Richard Welles, an inventor, and Beatrice Ives, a concert pianist, who both agreed that their second-born son was destined for greatness. “The word genius was the first thing I heard while I was still mewling in my crib,” he once said.

During Orson’s early years, Dr. Maurice Bernstein, a friend of the family’s, helped nurture the child’s talents. “Everybody was trying to cater to his intellectual and artistic growth,” McGilligan says. “They wanted to keep him pursuing art, and he’d put on little shows for his parents and then for [Bernstein].” The expectations were a lot to handle. “I always felt I was letting them down,” Orson said of his parents, who split before he was 6. “I trusted and feared their judgment. That’s why I worked so hard.”

His mother died of hepatitis when Orson was barely 9, creating a sense of “anguished loss,” he said, and McGilligan notes it left “the emotional hole in the center of a person the same way it is reflected in Citizen Kane.” Six years later, Orson would lose his father to complications of alcoholism.

Under Bernstein’s guardianship, he threw himself into theater and headed to Ireland, where he found success as a stage actor before setting his sights on Broadway. In 1938, at just 23, Orson wowed audiences with his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, an early peak in a career that would span nearly five decades and more than 25 films, including 1941’s celebrated Citizen Kane. “Hollywood offered him carte blanche and a lot of money,” McGilligan says. “He realized he could say what he wanted.”

His relentless drive led to a bad reputation at work, but his personal life was even more problematic. “He wasn’t going to be a family man,” McGilligan notes of Orson’s three marriages. “He just wasn’t a person that a wedding ring meant that much to.” Even his stunning second bride, Rita Hayworth — “a wonderful wife,” as Orson said — failed to tame him. “He was devoted to something other than women. He was devoted to his artistic pursuits,” McGilligan says, adding that Orson’s relationships with his three daughters, one from each wife, suffered. “He was a loving father, but he was an absentee father.”

Orson never divorced his third wife, Paola Mori, but began a 20-plus-year relationship with Oja Kodar after they met on the set of 1962’s The Trial. “She stuck by him through thick and thin,” McGilligan notes, adding that Orson eventually realized the error of his ways. “I’m not essentially a happy person,” he confessed hours before his death at 70 in a 1985 interview with Merv Griffin. Haunting him the most? “The regrets. The times you didn’t behave as well as you ought to have. That’s the real pain.”