Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

John Wayne: Getting to Know the Man Behind the Hollywood Legend

Today, Scott Eyman is a journalist, adjunct professor and author of numerous biographies covering actors and filmmakers from the Golden Age of Hollywood, but in 1972, at the age of 21 and armed with only the knowledge that he wanted to “write about the movies,” he found himself sitting with legendary Western star John Wayne. That meeting would lead, over 40 years later, to his writing the biography John Wayne: The Life and Legend.

“If I hadn’t met him,” Scott, who was born March 2, 1951, muses, “I probably wouldn’t have written the book. Over the couple of hours I sat with him, I found that there was an interesting gap between who he was as a human being and what he played. I mean, not 100% — there was definitely an overlap — but he was much more … thoughtful … as a person than his screen character was. He was much more contemplative than his screen characters. His body language was different as a person than it was on screen. So there were just all of these interesting differences between what he did and what audiences thought of him, and who he actually was.”

Noting that he had been a fan since the time he was a kid, memories still burn fresh of going to the local theater and watching all of those movies. “I was actually kind of young for John Wayne,” Scott suggests. “He belonged to an earlier generation and most of my friends thought I was kind of goofy, because I would go see The Sons of Katie Elder or Big Jake and things like that. I wouldn’t have thought of missing a John Wayne movie.” Just as he couldn’t have imagined spending five years of his life to come writing about him.

For more of our exclusive look back at the life and career of John Wayne, please scroll down.

Be sure to check out and subscribe to our Classic TV & Film Podcast for interviews with your favorite stars!

1 of 14

Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

It Started With a Letter

With no idea of how he was going to pursue his dream of writing about the movies, Scott began writing letters to everyone. “In that era,” he reflects, “there were a lot of guys sitting around in LA who weren’t working, who had had really interesting careers. I sent several letters to six or eight people, and Wayne was one of them. Although he was still working at the time, I figured, ‘Hell, why not start at the top?’ And I got a letter back from his secretary, Mary St. John. Now I had no credentials whatsoever; I was writing for an alternative weekly, but I guess I wrote a good letter. She wrote back and said if I was ever in California, I should call her.”

Two weeks later he booked the trip and made it shortly thereafter. Upon his arrival, he called Mary to let her know he was there. She said, “He’s shooting a TV show at CBS. What are you doing tomorrow at one o’clock?’ I said I could be there and she arranged it and that was it. I showed up and was ushered into his dressing room. There he was, smoking a cigar, which was funny in and of itself, because he was America’s most famous cancer survivor.”

2 of 14

NBCU Photo Bank

Making the Rounds With the Duke

While Scott was expecting a short meeting with the legendary actor, things went on for about 90 minutes with him asking questions and John Wayne answering. “What I didn’t know is that he hated to be alone,” he says with surprise. “He liked having people around him, and part of Mary St. John’s job was to fill up his day so that he wasn’t sitting by himself in his trailer, you know? Most actors don’t want to put the public anywhere near or around them, but he would talk to almost anybody rather than be alone. So I got 90 minutes, and every once in a while somebody would stick their head in the door and say, ‘We’re almost ready for you, Mr. Wayne,’ and he’d say, ‘I’m doing fine, I’m doing fine. Got my friend here.’ Finally the time came when he had to go to the set, and he invited me to come out with him. It was a 50th anniversary salute to CBS and Bob Hope was there, Jack Benny was there. And he takes me around, introducing me to all these people who are looking at me, like, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’ I didn’t have a pass and was taking pictures with my 35mm camera and they didn’t know who I was. Nobody wanted to say anything, because I was with John Wayne.”

3 of 14

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Believing in the American Dream

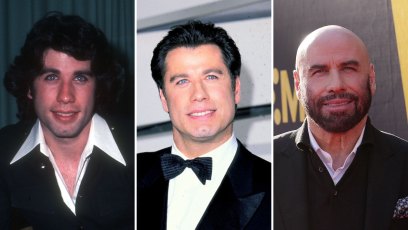

John Wayne was born Marion Mitchell (eventually changed to Robert) Morrison on May 26, 1907 in Winterset, Iowa, reportedly entering the world at 13 pounds. By 1916, the family had moved to Glendale, California, where he attended Glendale Union High School, doing well in both sports (particularly football) and academics. It’s also where he picked up his nick-name, Duke, given to him by a local fireman who called him “Little Duke,” because he was always accompanied by his huge Airedale Terrier, Duke. Not too pleased with the name Marion, he preferred people refer to him as Duke. All of this would put him on the road that would lead to his Hollywood career — and ultimately sustain his legend, despite his well known conservative views.

“Kate Hepburn was a flaming liberal all of her life and never deviated from it,” says Scott, “and she worked with him at the tail end of their careers in Rooster Cogburn — and she adored him. Most people, even liberals, loved working with him, because he was a very good actor and he worked hard. He was the first guy on the set and the last guy to leave. He was a pro’s pro and actors like that. He wasn’t phoning it in. Politically, she said he was reactionary. She said his political philosophy was based entirely on his own experience. Because he made it starting from nowhere — the family was lower middle class on its best day, and there weren’t too many good days in that era for him — why couldn’t everybody else make it? Completely overlooking the fact that, A, he was extremely handsome, was six-foot four, had a skill set that was remarkable and was a powerful locomotive. He was extraordinarily ambitious. Well, not everybody has that group of characteristics. There are people who work really hard and don’t have his talent. They’re not particularly talented in a way that’s going to bring them a lot of money, you know? And she said he just couldn’t grasp that. He figured, it’s America. If you work hard enough, you can make it.” Well … not necessarily.”

4 of 14

Southern California/Collegiate Images/Getty Images

Football is the Key

John attended the University of Southern California, where he actually majored in pre-law and played on the university’s football team. Notes Scott, “He never would have been able to go to college if he hadn’t gotten a football scholarship to USC, because there was no money. I mean, tuition at that point was probably $400 a semester or something. Not a lot, right? Well, forget it. They didn’t have it. His father worked as a druggist; in that era, you didn’t necessarily have to be licensed, because you’re working in small towns in Iowa and the Midwest and California. Nobody asked for a license. Hey, if you don’t kill anybody, you can work as a pharmacist. And his father always had a lot of trouble putting bread on the table. He never said a word against his father, but the man was not a success in life.

“On top of that,” he adds, “it was a bad marriage between his parents. They broke up early and divorced, and there weren’t a lot of people who got divorces in that era around World War One. So he went with his father and his brother went with his mother, and as a result she always had a hard on for him, because he decided to go with his father. So he and his father settled in Glendale and he was a natural athlete, had been a very big man on campus at Glendale High. He was head of the debating club, he was in the theater club, he wrote a sports column for the school newspaper and he was the star tackle on the football team, which was a great football team. That led to him getting a football scholarship to USC, where he had decided he wanted to be a lawyer. But then he would need a summer job, and when the guys on the football team needed jobs, they would go to work at Fox as laborers, because the head coach of the football team had an in at Fox. So that’s how he got in the movie business and that’s how he met [director] John Ford as a kid on the USC football team. And as he started to work at Fox, he got attracted to it.”

5 of 14

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Goodbye Football, Hello Hollywood

Two years into college, he lost his football scholarship and, as a result had no choice but to drop out of school. “He busted a shoulder surfing and nobody needs a tackle who can’t block, so he got cut,” says Scott. “As a result, he couldn’t afford to pay the tuition, which is why he had to drop out. So then he decided to stick around Fox and go into the movie business. It’s that John Lennon lyric, life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans. At Fox he became a laborer, an assistant camera man, he did make-up — he did everything, because he was just a kid trying to make a living and Ford took a liking to him and made him a part of his crew. Gradually Ford gave him some small parts — walk on parts, nothing special — because he had a nice face. Then he got the job working for Raoul Walsh on The Big Trail, because it was 75 bucks a week and he had been making 15 bucks a week. In 1929 or 1930, that’s good money for a kid with no college degree who wants to be a movie star. And, of course, it bombed and he spent the next 10 years basically tap-dancing, making five or six-day westerns. But it was a living and during that time he got married and had kids. And then, finally, Ford came around and said, ‘Let’s do Stagecoach.’”

6 of 14

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

‘Stagecoach’ Changes Everything

Released in 1939 (the same year as both The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind), Stagecoach is looked upon today as a seminal Western about a group of strangers riding on a stagecoach through what is deemed dangerous Apache territory. Director John Ford, despite protests from studios and producers, refused to make the film without John Wayne. The gamble obviously paid off, with Ford commenting at the time, “He’ll be the biggest star ever, because he is the perfect ‘everyman.'”

Enthuses Scott, “What you see is a guy who doesn’t have a great hand of cards at any one time, but he’s working and working and getting better and better at the craft of acting. So when Ford finally says, ‘Let’s do Stagecoach,’ he was ready. He’ learned how to act. He’s learned how to react. He’d learned how to work a scene with another actor He’d become a professional.”

7 of 14

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Mastering His Work Ethic

Points out Scott, “By the time of Stagecoach, he’d become a professional, and that’s a real tribute to his work ethic. Like I say in the book, he was a natural movie star. He was not a natural actor. He had to learn how to be an actor, but he was a born movie star, because he fills the frame. When he’s in the shot, you don’t really look at anybody else. Well, you can’t teach that. That’s something you’re born with. On the other hand, if that person opens their mouth and you have to look away because they’re so awful, then that’s a problem. But not for him. He put in years of hard work; nobody worked harder. That work ethic really stunned Ron Howard years later when they made The Shootist, as he told me.”

In an interview with the Huffington Post, Ron explained that he had asked John Wayne to run lines with him during the making of the film, which shocked the Duke as that was something no one had ever asked him to do before. Said the actor turned director, “I always admired him as a movie star, but I thought of him as a total naturalist. Even those pauses were probably him forgetting his line and then remembering it again, because, man, he’s The Duke. But he’s working on this scene and he’s like, ‘Let me try this again.’ And he put the little hitch in and he’d find the Wayne rhythm, and you’d realize that it changed the performance each and every time. I’ve worked with Bette Davis, John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, Henry Fonda. Here’s the thing they all have in common: They all, even in their 70s, worked a little harder than everyone else.”

8 of 14

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Dealing With Success

After Stagecoach, John Wayne went from success to success, films like Red River, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Quiet Man, Rio Bravo and The Longest Day turning him into a true Hollywood icon. But what did that kind of success have on him? “He had conflicting impulses,” details Scott. “There’s a moment when he’s doing things like The Long Voyage Home for Ford, where he’s playing a Swedish sailor and doing rather well, actually. But it’s an art movie. It’s not a commercial movie. And he would talk about how he wanted to do all of these different parts; he wanted to play this an he wanted to do that. He wanted to do serious acting in serious movies. Now Harry Carey was his dear friend. He’d grown up watching Harry Carey’s Westerns back when he was in Glendale in the 1920s. And Carey’s wife was a dear friend and worked in a number of pictures with Wayne, including The Searchers. She said, ‘What are you talking about?’ Look at Harry’ — who was sitting there — ‘What do you want Harry to be in a movie?’ And Wayne said, ‘Just him, Harry Carey.’ ‘Exactly. And you should just be John Wayne.’ Now, could Harry have done other things? Of course he could, but that wasn’t what Harry was selling. He was selling that kind of honest approach to a scene and a honest approach to a character, and he rarely played a heavy. Usually he played good guys with a rough hewn sensibility. So I think that was a crucial conversation for him, because he had been talking about doing more than Westerns or men or action movies.

9 of 14

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

“All of that,” Scott elaborates, “kind of rocked him back on his heels. Wayne was a very good actor and he didn’t just do one thing. I mean, the guy from Red River and the guy from She Wore a Yellow Ribbon have 180-degrees between them, you know? And they’re both beautifully acted, but you couldn’t mistake one character for the other. Now it’s true that later in his life, especially in the ’60s, he kind of fell into a groove. But in the ’30s and ’40s, there’s not much of a groove there. He’s playing all sorts of different things, but even then he’s playing guys whose word is their bond, who don’t go back on their word. If they make a mistake, it’s an honest mistake and not made for small reasons. And those are the things he stuck to because of the conversation he had with Olive Carey. But later on, he wasn’t challenging himself at that point, and the directors who did challenge him were dead or retired. Now they were all deferential towards him. He was the boss on the set at that point. If he was working for John Ford or Howard Hawks, they were the boss and he would say, ‘Yes, sir.’ He wasn’t going to give them a hard time, because they were better directors than he was and he was scared of them on some level.”

10 of 14

Getty Images

‘The Green Berets’: Things Begin to Go South

If there was a turning point in John Wayne’s career, it was probably 1968’s The Green Berets. In it, Wayne plays Col. Mike Kirby who allows a reporter (David Janssen), who lies in opposition of the Vietnam War, to accompany his team on a top secret mission, the results of which convince him that the U.S. is exactly where it needs to be. Right wing politics for sure.

“I think The Green Berets cost him an entire generation of the audience,” Scott suggests, “but he didn’t care, because he was putting his money where his mouth was. He produced that picture himself and it did alright. Not a huge money maker, but it didn’t lose anything. He was going to tell it like he saw it, and he thought Vietnam was a wonderful idea and that we had to stop the commies or they’d overrun us.

“Nobody believes that now, and nobody really believed it then,” he continues, “but there was a faction that did. Right after The Green Berets, True Grit comes out and that helps with some of the fans that he lost. But I was 18 when The Green Berets came out, and I thought it was just a godawful picture. Even aside from his politics, it’s a World War II picture he’s making about Vietnam, and they’re two totally different things. But he just didn’t care.

11 of 14

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

“But you could see as the ’60s became the ’70s, his box office is beginning to deteriorate. Even though True Grit was a huge success, and Big Jake made money, nobody was going to retire off the returns from [modern cop] films like McQ or Brannigan or, for that matter, The Shootist, even though it’s a wonderful picture. He had not brought a younger audience into his pictures. Now most 65-year-old movie stars don’t, let’s face it. When you get to be a certain age and you’re a star, basically you’re working the audience you already have. It’s very hard to get 20 year olds, because they look at you and they see their grandfather’s hero and they don’t care about that. That’s the problem that George Clooney and Bruce Willis are having now. Every big movie star has the same problem, and Wayne was having that problem.

“The other thing is that Westerns started to croak. He tried to do a cop film, but he’s the world’s oldest detective. He’s just too bloody old; he’s not 35-year-old Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry, and that’s what he’s trying to do, but his timing is off. And with Westerns starting to suck wind and losing their audience, plus the audience got old and kids were not going to see Westerns, that also had a big impact on him, because that was his fallback genre. He was gradually painted into a corner by the time of The Shootist and I don’t know what he would have done, frankly, had he not gotten sick and ended up dying. Where was he going to go? I don’t see him doing television. He could have done character parts; and I don’t think he would have retired. Movies were his passion, more than his wives or anything.” For the record, he was married three times and had seven children.

12 of 14

Getty

His Battles With Cancer

John Wayne was a chain smoker and addicted to nicotine. In 1964, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which resulted in his entire left lung being removed. Five years later he was declared cancer free — along the way warning the public to get preventive examinations and coining the phrase “The Big C” for the disease. Sadly, it returned in the form of stomach cancer, which claimed his life on June 11, 1979.

Scott had the chance to see John Wayne again a few years after their first meeting, coming to the set of what would be his last film, 1976’s The Shootist. “He was clearly not his best,” he reflects. “You could hear it in his voice sometimes. He’d been sick and they’d had to shut the picture down for two weeks, because he’d gotten a lung infection from one of the shooting locations. In any case, he looked at me and kind of nodded and I nodded back. I knew that he recognized me, but he didn’t know from where. I watched him work a scene with a barber, but there was a sense of laboring there, because of fading health.”

13 of 14

ABC Photo Archives via Getty Images

The Loss of a Legend

As noted, John Wayne died in 1979, and yet here we are, 40 years later, and his legacy still lives on — despite views that alienated so many (but, to be fair, were embraced by many others). “It was like the loss of the last Redwood in the forest,” Scott smiles. “Guys like Gary Cooper and Clark Gable started dying in the late ’50s. Guys of that level of stardom; who guaranteed a certain level of commercial success. Those guys started dying, and dying young — Tyrone Power was 45, Gable was only 59, Gary Cooper I think was 60 — because they all smoked, they all drank, nobody exercised and they didn’t take care of themselves. When those guys started dying, they didn’t get replaced. And there was no one to replace John Wayne. He was the last of the generation of guys who became huge stars in the ’30s and transcended all the changes of style and content that afflicted the movies any time over the next 30 years.

“Wayne lasted longer than they did, because he lived longer than they did. But none of those guys were affected by flops. They all had stiffs, but it didn’t matter, because they were Gary Cooper and Clark Cable. And it didn’t matter with John Wayne up until the very end, because they guaranteed a certain level of audience attendance. Did every picture make money? No, but very few laid down and died.”

14 of 14

Getty Images

As to the enduring nature of the memory of John Wayne, Scott comments, “The films are still in heavy rotation on cable. The John Wayne birthplace museum in Winterset does very well. He’s transcended his own generation. I think he came to embody a kind of mythical American that had existed before in James Fenimore Cooper, pulp novels and things like that. He incarnated it to a greater extent than anybody had before or after. A kind of rough hewn frontier sensibility, emotionally honest, limited in some respects, but a man who could transcend his own limitations under the pressure of the moment and rise above their prejudices in a way that he wasn’t always able to do in life.”