Courtesy Adam Nedeff

The Real Story of the Biggest Quiz Show Scandal of the ’50s: How it Changed Game Shows

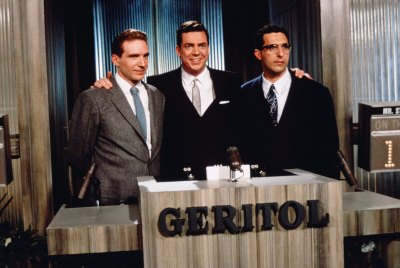

In 1994, Robert Redford directed Quiz Show, the critically acclaimed story of a corrupt TV game show that illegally fooled the public and altered the lives of two men, played by Ralph Fiennes and John Turturro. Nominated for five Academy Awards (including Best Picture) and four Golden Globes, it’s a powerful story that also happens to be based on a true situation from the 1950s that changed the nature of television game shows to this day.

Adam Nedeff, game show historian, author of numerous books on the subject and someone who has actually worked behind the scenes on such shows as The Price is Right, Idiotest, Double Dare and Wheel of Fortune, can certainly attest to that fact that all these decades later things have never gone back to the way they were.

“I’ve worked as a prize coordinator on game shows,” he explains, “and we have a rule on the books that we have to get rid of the prizes that we have to give away, because they want to make sure that nobody working on the show is keeping them for their own benefit. So at the end of the season, anything that hasn’t been given away as a prize, we have to send back to the manufacturer or, if the manufacturer doesn’t want it, we have to give it to some charity. Another thing is, I have to be kept very separated from the contestants because of the job I do.”

“On a show that I worked on, and I felt bad about this, but this kind of thing happens,” he adds, “I was in the same room at a restaurant as a contestant who was being considered for the show. I didn’t realize that until I was already there. And once it became clear that he was going to be a contestant on the show I was working on, they ended up calling him and telling him not to come in, because it would be a problem if he was a player. So it is very richly monitored who you are and who you’ve crossed paths with and whether or not you’re going to be a contestant on a show.”

Sounds extreme, but it’s warranted. David Hofstede, author of What Were They Thinking? The 100 Dumbest Events in Television History, explains, “It’s a story about more than greedy sponsors, desperate producers and average Joe contestants who were tempted by overnight fame and the kind of money that changes lives in exchange for a compromise of integrity, that, they were told, no one need discover. The timing of the revelations, just as television emerged from its formative years into a promising adolescence, forever changed how Americans looked at that new electronic piece of furniture in the family room.”

Please scroll down for much more on the quiz show scandal.

Everett/Shutterstock

Library of Congress

Alka Seltzer

Alka Seltzer

AP/Shutterstock

Courtesy Adam Nedeff

Ac/AP/Shutterstock

Hollywood Photo Archive/Mediapunch/Shutterstock

Hh/AP/Shutterstock

NBC

Courtesy Adam Nedeff

TV Guide

Dg/AP/Shutterstock

AP/Shutterstock

Snap/Shutterstock

Wca/AP/Shutterstock

Woa/AP/Shutterstock

Anonymous/AP/Shutterstock

AP/Shutterstock

Courtesy of Adam Nedeff

AP/Shutterstock

Hollywood/Wildwood/Baltimore/Kobal/Shutterstock